Rev. Deborah Duguid-May and Dr. M. Elizabeth Thorpe discuss Judas. They discuss both the Biblical depiction of him and the recently discovered and translated non-canonical Gospel of Judas.

Transcript

DDM [00:03] Hello and welcome to The Priest and the Prof. I am your host, the Rev. Deborah Duguid-May.

MET [00:09] And I’m Dr. M. Elizabeth Thorpe.

DDM [00:11] This podcast is a product of Trinity Episcopal Church in Greece, New York. I’m an Episcopal priest of 26 years, and Elizabeth has been a rhetoric professor since 2010\. And so join us as we explore the intersections of faith, community, politics, philosophy, and action.

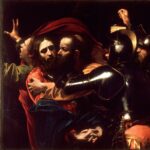

DDM [00:40] Welcome. For anyone familiar with Christianity, they would have heard of Judas, the one who betrays Jesus and hands Jesus over to the state. Judas is a character that has also been portrayed in secular history as the traitor, the betrayer, all for money. In the Gospel of Luke, we read that Satan entered into Judas and drove him to betray Jesus. In the Gospel of John, he writes that he, one of the twelve, is a devil.

DDM [01:11] St. Matthew records that Judas hung himself with guilt for what he had done, and in the Book of Acts, we are told that Judas’ belly was ripped open and he died in a ghastly manner. In fact, even the Judas kiss has become a famous phrase. This is by far the dominant narrative and interpretation we have, and certainly been the official narrative of the church historically.

DDM [01:37] And yet I think sometimes people wonder if there’s more to the story. We know our own human need to scapegoat and make someone the villain, and so we find ourselves wondering, what perhaps in the story are we not being told? Was there another perspective to the story? In our podcast that Elizabeth and I did on Mary Magdalene, we spoke a bit about many of the other Gospels that were written, many of them around the 2nd century.

DDM [02:06] The Gospel of Judas, according to the historian Irenaeus, was written around 180 AD. And although the original was probably composed in Greek, the version that we have is a Coptic translation. It was discovered in a papyrix codex or book in Egypt in the late 1970s. It was probably originally composed in Greek, but the version, as I said, we have as a Coptic translation.

DDM [02:35] And translation of this Coptic version only began in 2001\. And in 2006, it was made available in printed form for the very first time to the public. So we’re dealing with a very recent development. There is a loss of text due to damage to the papyrus, but it’s really incredible, I find myself, to think that this gospel, after being lost for 1,600 years, is finally found and re-given to the world.

DDM [03:12] And once again, like the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, this Gospel is written at a time when there were still many theological interpretations of Jesus, many different ways of understanding Christianity, and doctrine had not yet been formed into what we have today. So, this Gospel, the Gospel of Judas, records the conversation that Jesus had with Judas over one week, right before the Last Supper. And there’s a couple of very unique perspectives in this Gospel. Jesus is portrayed in the traditional four Gospels we have in Scripture as being very solemn, under great pressure during this week, when he literally musters all his courage and strength to set his face towards Jerusalem, and what he knows lies ahead of him.

DDM [04:04] But in the Gospel of Judas. There is joy in this Jesus at this time that almost wells up within him, and it almost comes out in this like carefree childlike laughter. So in contrast with the serious piety of the disciples, Jesus in the Gospel of Judas is laughing at them, telling them not to take things too seriously. Don’t try so hard to be quote-unquote right, because God is working out something much greater than any of them perceive.

DDM [04:37] In the Gospel of Judas, the other disciples become angry with Jesus for challenging them and their egos or their pride, whereas it is Judas in this Gospel, not Peter, who provides the confession of who Jesus truly is. Judas also sees Christ for who he is as the one, and this is an interesting perspective of how Judas sees Jesus. The one who comes from the primordial mother who is before all else. Judah sees Christ not as the tribal Israelite or Hebrew God, but as the seed which comes from the womb of all.

DDM [05:19] Now this is very different, I think you would agree Elizabeth, than the confession of Peter who sees Jesus as the coming Messiah, an anointed one. And I think we also must remember that at this time any books which were naming God as feminine were largely not being included in the canon of scripture. Now in the Gospel of Judas, because Judas can see Jesus for who he truly is, Jesus pulls Judas aside and asks him this crucial question. What is more important to you?

DDM [05:53] Belonging or the kingdom of God? And will you want the kingdom of God even if it means you lose your place in this inner circle of disciples? What Jesus is asking him is, will you live out your calling even if it results in the destruction of your reputation? Even if you are cursed by future generations?

DDM [06:17] The other disciples in the Gospel are far more interested in Jesus as their tribal national God, rather than God for all the world and the establishment of a far greater kingdom beyond the boundaries of Israel. And in this Gospel, the other disciples are the ones who will use the name of Jesus to lead many astray. And so in the Gospel of Judas, he makes the choice to follow his calling and destiny just as Jesus follows his. His calling is the one not who will betray Jesus, but who will hand over the body of Jesus in order that Jesus may fulfill his calling.

DDM [06:59] And so we can see that certainly this is a very different interpretation from the other Gospels, but it also for me reminds us of the complexity of how Judaism was being understood and all the different competing groups and theologies at the time of early Christianity. and how the life and death of Jesus was being seen and experienced or interpreted in many different ways.

MET [07:26] That is all so interesting. I do not have the theological background to talk specifically about all the different gospels.

MET [07:37] That’s not my thing. But what I can talk about is story craft. And as a writer, as somebody who studied a lot of literature, as somebody who appreciates a good story, I feel like Judas is pretty indispensable. Let me clarify what I mean by that.

MET [08:02] I’ve always found Judas really interesting, and I’m not going to lie. That’s because I have always found the villains of stories to be way more compelling than the heroes. One of the reasons I love Shakespeare so much is because I find Macbeth and Iago to be such fantastic love-to-hate them kind of characters. You know, I think in my senior year in high school, I wrote a whole paper about how, you know, if you don’t have a – it was about Hamlet or something, but like if you don’t have a good villain, that makes the hero, right?

MET [08:34] The hero doesn’t exist without the villain. And in many ways, Judas is kind of the most interesting bad guy of them all because his portrayal was so profound and had kind of a large impact. And that’s – you can say that theologically, you can say that historically, but once again, I’m interested in a storytelling aspect for a second.

DDM [08:50] Right, right, right.

MET [08:53] And this is in a literary sense, right? When Dante reaches the last level of hell in the Inferno, Judas is one of the three betrayers at the heart of hell because his is the worst sin of all, right? Like that’s the ninth level of hell in Dante’s Inferno. It’s Judas and a giant mouth.

MET [09:10] The Western world has long understood Judas to be the bad guy to top all bad guys. So I’m pretty fascinated by some of these kind of, and it’s interesting that you say the translation was in the early 2000s, because the timing is interesting.

MET [09:24] I’m pretty fascinated by some of these kind of postmodern attempts to contextualize, if not rehabilitate Judas. And these kind of go hand in hand with what we’re talking about with this gospel, because it’s this notion that he was not just some kind of stand in for a traitor, but a fully fleshed out character. So this relates, but give me just a second.

MET [09:46] In my propaganda class, we talk a lot about myth and narrative, because these are really powerful and persuasive things. The idea is that there are certain stories, myths, if you will, that are so ingrained in a culture that you just assume they are true. It does not matter if they are true, because you behave as if they are. The reason this is important in something like understanding persuasion is because if you appeal to a story that can be highly persuasive, that everybody already agrees on, then you’re starting from a point where we’re all in the same boat, we can all head in the same direction, because

MET [10:28] you’re starting with that common starting point. You’re making an argument that starts with something your audience already says, yes, I’m with you. It’s easier to go that journey with you. So let me give you an example.

MET [10:38] Let’s start with the American dream. The American dream, right, if you had to define it, is pretty much that if you work hard and keep your head down, you’ll be able to succeed in life and get your house and your 2.4 kids and a dog and a white picket fence and whatever else you want, right? Like we know this.

MET [10:54] Now, when I say this, often my students scoff, but I tell them a part of you believes this. I know that for a fact. And I know that because you are here. Some part of you believes that if you go to school and get a degree and work hard, things will be better for you, right?

MET [11:11] Like you’ve shown up. I know that you’re invested in this. And we talk about that on a small scale too. They believe if they work hard, they deserve success.

MET [11:20] So if they put in 15 hours on a paper or project, they think they deserve credit. If they get a D-minus on such a project and they come to me to talk about it and say, but Dr. Thorpe, I worked for almost 20 hours on this. And I say, those must have been 20 crappy hours. They would be both crushed and livid.

MET [11:41] B`ecause there is this idea that if you work hard and long, you should be rewarded. That’s the American dream. That’s the myth. And it is pretty important that most people believe that myth because what would happen tomorrow if we all woke up and realized that our work does not guarantee anything?

MET [12:00] The economy would come to a grinding halt because a lot of people would just stop working. We have to believe in the American dream to keep this country going. If we just woke up one day and realized, actually, work doesn’t guarantee much at all, we would stop. So it does not matter if these things are true. We are invested in them as if they are.

MET [12:25] So, okay, all of that is about myth and narrative. The narratives that are part of these myths are foundational not just to America, but to Western Civ. There are certain narratives, certain stories that are just at the core of who we are as a people.

MET [12:40] And I mean, half the world is invested in this. And even beyond that, there’s some universals within that. Things like “the hero’s journey,” or “the quest,” or stories of “the trickster.” These are everywhere. And the reason I bring this up in a story about Judas is because I want to talk about archetypes. In Western civilization, there are only certain stories that we tell. And because there are only certain stories, there are only so many characters. In many real ways, we just keep telling the same stories over and over again, and just kind of popping names in and out while we use and reuse the same characters.

MET [13:22] These are called archetypal characters. You may balk at that because all these characters seem different because of context and development. But the truth is, we’ve been telling pretty much the same dozen or so tales since the time of Aristotle. And with the exception of a few innovations in the postmodern era, we’ve been using the same characters to do it.

MET [13:43] These are characters like the hero, the wise old man or woman, the trickster, the princess or damsel in distress, the femme fatale, right? In whatever movie or book or whatever, you can say, oh yeah, I know who these people are.

DDM [13:59] Right.

MET [14:00] The reason Judas plays into this conversation so well is because as we have changed as a culture, Judas has gone through different manifestations of archetypes. Judas spent a long time as a straight-up villain. He was sort of a big bad wolf kind of a character, right? Evil, focused on one hero, and in some ways a bit seductive, not in a physical or sexual sense, but in a more persuasive and intellectual sense.

MET [14:26] He was the ultimate traitor and bad guy. But as a story-consuming culture, we have not been happy with that bland archetype. That wash of just straight-up evil doesn’t make sense to us anymore. We demand context.

MET [14:41] We demand backstory. We demand to know why Judas is the way he is. And as Judas’ story has developed, be it through pop culture or the Gospel of Judas or even through literature, Judas has transitioned through a few different archetypes. He’s gone from being the ultimate villain to something different, depending on who you ask.

MET [15:02] To some people, he’s more of an anti-hero or a trickster now, and that is absolutely fascinating to me, because Judas hasn’t changed. The story hasn’t changed. But for some people, the core understanding of who this character is, has. And not everyone would have him at the center of the Inferno anymore.

MET [15:23] And that is just wild to me. And most importantly, it says something about us. Because it isn’t enough to just say, oh, here’s this character, blah-biddy, blah-biddy. It’s a conversation.

MET [15:34] No. It is not that we think about him for just randomly bad guy, that he has transitioned into something else. The important question is what this says about us. What do we want or need from this story?

MET [15:51] What do we want or need from this character? How do we see ourselves reflected here? And I think that’s the real question that as a storyteller, this is really interesting to me.

DDM [16:03] No, absolutely. And I think that for me is also the real gift of us finding these new manuscripts. I mean, the fact that this one was written probably around 180 AD, you know, there were different, even back then, there were these very different competing narratives, you know, so we’re only just really beginning, I think, to understand and appreciate the extent to which there was this huge diversity in thought, in understanding of some of these central characters, which, as you say, we’ve only had one way of seeing in the past, and that there was not just also one way in which Jesus was being understood and experienced.

DDM [16:46] You know, and I just think for myself that there’s such a danger in thinking that there is only one way of seeing things, because the reality is we all see, perceive, and understand something depending on who we are, as you were saying, in our own context. And so hearing these other voices, whoever the other voice is, you know, is really so important.

MET [17:09] I had a friend in grad school who was an avowed, well, okay, he was an avowed atheist. I had a lot of friends in grad school who were atheists.

MET [17:17] Grad school is a place where you find a lot of that. He knew I was religious and that was not an issue. We talked about theological things and we had questions for each other and there was never any ill will or tension about any of it.

MET [17:30] We were just good friends and we felt like we had a lot to learn from each other. And if I might add, that’s exactly what it should be like between people of different backgrounds and philosophies.

DDM [17:39] Yes. Always.

MET [17:41] Like we just had a great time, you know, figuring each other out. But one day, we were talking about some of the nuances of the story in question. And he said he always thought the story of the crucifixion got it a bit wrong, bold claim. He said he thought Judas made the ultimate sacrifice.

MET [18:00] And I was a bit taken back by that because in my mind, Judas was treacherous. Thinking of him as doing anything Christ-like seemed a bit blasphemous. This probably showed on my face because, you know, I was shocked, but I was going to let him finish. And he said, there’s no reason to think Judas changed his mind on Christ’s personhood.

MET [18:19] Judas may well have still thought Christ was divine or the Son of God or the Messiah. Judas might well have realized who he was betraying. The question is why? Did he betray Christ because he felt Christ was ineffectual, because Christ wasn’t exacting the kind of change Judas wanted to see?

MET [18:37] There are a lot of guesses as to why Judas turned his back on Jesus, but he said not many of them are that Judas stopped believing. Which, he continued, means Judas may well have known what he was doing. Judas may have realized that there comes a time when sacrifices need to be made, and he made one. And if that is the case, then Judas knew where he would be heading, like to an eternity of damnation, in order to do the right thing for all the world.

MET [19:04] And that, my friend said, is a heck of a sacrifice. Now, I had no idea what to say to this, because I had never heard anything like that. And it seemed so antithetical to everything I knew, and pretty heretical. But that was 20 years ago.

MET [19:19] And I’ve had time to sit with that conversation a lot. And while I’m not prepared to make any statements like what my friend did, I am prepared to make a guess as to why a narrative like that might be appealing. The story of the gospel is really tough. In a lot of ways, it doesn’t make sense.

MET [19:41] It’s really hard to latch on to. We’re supposed to connect to, once again, characters, right? We’re supposed to connect to this person, this character. who is God incarnate, perfect in every way, who loves so much and so deeply that he died for all of us and then miraculously came back from the dead.

MET [19:58] And this is supposed to help us make sense of the world? Sis, please, how is this helpful? If you tell this to the average person with no context, they will move right along. The thing about perfection, the thing about the story, the thing about salvation is that it is unattainable.

MET [20:17] Why bother worrying about connecting to a figure that is unattainable? I mean, that’s why I’m not particularly interested in a lot of archetypal good guys. They’re uninteresting and I don’t have any connection with them. But Judas is 100% flawed and human.

MET [20:33] If we think about sacrifice in human terms, it’s understandable. My friend wasn’t trying to be blasphemous. He was trying to put the story in terms he could make sense of. A god who came to earth and was perfect and then died doesn’t make sense.

MET [20:47] A man who is willing to put his life on the line for others does. And even the act of betrayal makes Judas more accessible. Churches have done a lot of damage by making God and Jesus into these up-on-high, untouchable, and holier-than-us heavenly beings, when what we need is somebody who gets us. That’s what my friend was getting at.

MET [21:08] There is no way that the Jesus who has been portrayed by the church for the last millennia or two would get us. He’s just too much. But Judas is a sinner. He made big mistakes.

MET [21:23] That’s something people like my friend can latch on to. And once again, as we read and reread the stories, the question is less, what do these stories tell us? And more, what do these stories tell us about ourselves? And this is one of those situations where it doesn’t matter what the theology is or what the manuscripts say, because the story has been told in a particular way for a very long time.

MET [21:46] And the narrative matters way more than the primary source or the preacher or whatever, kind of like the concept of myth that we were talking about. Because we are invested in the story and behave as if it is true in that way. There are certain things we have been taught to believe about people like Jesus and Judas, and that’s the prevailing narrative so that’s how we live our lives.

DDM [22:14] Very interesting, eh? So I guess for me, I do need to always work with the primary text. So what I find interesting, and especially coming out of what you’ve just shared there, is in the Gospel of Judas, Judas doesn’t actually see Jesus as the Jewish Messiah. He sees Jesus as one who comes from a far more universal God, the Primordial Mother. So he and the disciples see Jesus very differently.

DDM [22:43] Judas also in the Gospel of Judas doesn’t betray Jesus, but actually is the one who helps him fulfill his destiny and sets him quote-unquote free from the physical body. And in the Gospel of Judas, Judas, by doing this, ends up sacrificing his reputation. That is really what he loses, his place in that inner circle, his historical legacy. Because, and he’s prepared to do this, because for him he’s doing something far more greater.

DDM [23:14] He’s being true to his own calling. And so he chooses the kingdom of God over his own personal reputation. You raised the issue of perfection and I just want to come back to that because, you know, in the Gospels, it’s so interesting how, you know, we end up obviously with these translated texts and we’re looking at them through our Western frameworks, but in the Gospels, the word used for perfection is telios, which doesn’t mean perfection in the sense of how we use that word in English.

MET [23:46] Does it mean without flaw?

DDM [23:46] No, rather telios means to be complete. It means to be whole, to be fully mature or developed.

DDM [23:54] So really the idea of Jesus is that he was a person who was fully complete. He was fully whole. He was integrated. So when the Gospels call us to be perfect, telios, again, it really means to be able to grow into being completely who we were called to be, to be whole people, to be integrated with integrity.

DDM [24:18] And again, that Hebrew word for perfect, which is tamim, means, again, to be whole, healthy, and having integrity. And I think, you know, you hit the nail on the head where we have created often this very unhealthy narrative about God based on very poor translations that end up with this unhealthy, unhelpful, ideology. You know, God incarnates, takes human flesh to show us what it looks like for a human being to be whole, to have integrity, to be a complete human being. And yet how we’ve distorted that so often, you know, in theology.

DDM [25:02] And I guess for me, that’s why the Gospel of Judas and all the other Gospels, in some ways, that’s what they’re trying to grapple with. What does it mean for our choices, although they may be very different, I mean, Judas makes a very different choice from the rest of the disciples, but what does it mean for our choices, even if they’re different from everybody else, to be choices that for us have integrity? You know, what does it mean when the way we see things and experience things may be radically different? But the question is, do they lead us into a greater sense of wholeness and health?

DDM [25:39] What perspectives enable us to live into a greater wholeness? And what perspectives have we been taught or have we internalized that actually break us and do damage to us as human beings? And I think those are some of the questions that are also important for us to look at when we read any gospel, but also when we look at any theology. Is it leading into greater wholeness, integrity?

DDM [26:03] Is it enabling us to become more fully human and more full human beings? Or does it really cause unhealthy damage to myself and others in this world?

MET [26:16] So I want to kind of sign off with this. Some of the things that Deborah and I have danced around really for the last few months are questions of the differences between how we say what we believe and how we do what we believe and how we integrate what we believe. And I feel like some of our last few episodes have really kind of brought all of this into a very synthesized conversation. So I want to kind of bring some of this to a head.

MET [26:54] You know that I am a communication scholar, so I’m very interested in the words and the language that we use. And today I was talking about being a storyteller, right? It’s just All my life I’ve been interested in what we say and how we say it and the narratives we weave. And you know, Deborah is just such a fantastic purveyor of theological knowledge and doctrine and just such a great teacher.

MET [27:19] And one of the things that I think we are trying to do is talk about how we tell stories and how we tell stories about ourselves and how we tell stories of our relationships. and the way that we as people dialogue and how that shows up in our theology and how that theology shows up in our life stories. So, when we do episodes like this, that seems, well, just kind of a one-off, well, it’s just about Judas, how does that – it’s not just about Judas, it is about who we are as people. And that’s kind of what – I want that to carry us through as we look through these next few episodes, because we’re going to be looking at some very specific topics.

MET [28:05] But I don’t want you to think of this as a lesson on Judas. I want us to think broadly in terms of what does this lesson say about us and how are we communicating ourselves to each other? Do you feel like that’s a pretty good way to?

DDM [28:19] Absolutely, absolutely. So when we look at this topic, for instance, today, how do you understand who you are? How do you understand your calling? That may be very different from the way other people understand theirs.

DDM [28:32] That’s okay. How are you understanding what is sacred? Maybe you name it in ways very different from those around you. That’s okay.

DDM [28:41] You know, it’s that really pushing and allowing other stories for us to reflect on them and say, so where am I? Who am I?

MET [28:51] Yeah. I think that’s so important.

DDM [28:52] How does that influence the choices that I’m making? You know, because the reality is, is integrity is the most important thing. So, you know, Elizabeth and I have some very similar values.

DDM [29:04] We live them out in very different ways. Yeah, absolutely. And that’s the beauty and the diversity of this world in which we live, is that there’s so much space for diverse action, diverse belief systems, diverse ways of understanding, and the more we come into conversation with one another and our ideas, the more we can grow and spark these own inner journeys that we have within ourselves and in relationships.

MET [29:30] Yeah, so that’s what we hope you’ll keep in mind as we move forward with some of these kind of singular topics, is we’re not thinking about when we did Mary Magdalene, it wasn’t a lesson on Mary Magdalene, it was a lesson what these people say to us and about us.

MET [29:40] Okay. Well, thank you so much for joining us and we look forward to future conversations.

MET [29:58] Thank you for listening to The Priest and the Prophet. Find us at our website, https://priestandprof.org. If you have any questions or concerns, feel free to contact us at podcast@priestandprof.org. Make sure to subscribe, and if you feel led, please leave a donation at https://priestandprof.org/donate/. That will help cover the costs of this podcast and support the ministries of Trinity Episcopal Church. Thank you, and we hope you have enjoyed our time together today.

DDM [30:25] Music by Audionautix.com

.